Organizations should not be afraid to humanize technology.

Imagine interacting with a domestic robot. You might give it a list of tasks to complete while you are at work and — without worrying about how, and in what order — the tasks would be completed. Over time, you would begin to trust its judgment, provide it with an identity and maybe even a personality.

This raises the controversial notion of anthropomorphization — the attribution of human traits, emotions or intentions to nonhuman entities — or “things.” While some decision makers are skeptical of this approach, Jim Davies, research director at Gartner, says that anthropomorphizing things can help organizations plan for a world where customers, citizens and workers are not necessarily human.

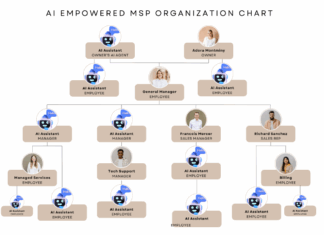

“Anthropomorphization should not be an end goal, but a human computer interface approach can facilitate efficient, trusted and pleasurable transactions,” adds Davies. “By perceiving things as ‘customers’, ‘citizens’ and ‘workers’, IT and business leaders can consider a strategic approach to how things relate to people, organizations and one another.”

The pros and cons of anthropomorphization

There are many advantages to using anthropomorphic approaches when designing things. Anthropomorphic techniques that use human language and symbolism, and devices such as virtual assistants and chatbots, can promote natural interaction, trust, learning and empathy between artificial intelligence (AI) software/models and humans.

That’s not to say that a strong anthropomorphic approach is always best. In sensitive situations (such as a robot providing medical advice to a user) overly anthropomorphic approaches could make patients uncomfortable and prevent them from disclosing essential information.

Anthropomorphization also offers another opportunity. This is the notion of obtaining digital customer/worker/citizen feedback from the “voice of the thing” (VoT). Humanizing a connected thing creates the opportunity to obtain feedback from it in the same way we would from a human being, complementing existing human feedback.

All things are not equal

Another key consideration is determining whether a thing has a “voice.” It’s important to distinguish between simple reporting of operational Internet of Things data and what would be considered the VoT. The key distinction is that VoT requires some form of intelligence that drives thing opinion.

“The VoT doesn’t just report facts,” says Davies. “It enriches them, contextualizes, them and provides a rationale for the feedback. While the baseline for thing feedback is simply factual and event-based reporting, the VoT should be associated with something more — encompassing opinions, beliefs, contextual enrichment of narratives and exposition of rationales around balancing short- and long-term goals. That’s the difference between operational reporting and the VoT for the various types of feedback — whether direct, indirect and inferred.”

The road ahead

“The VoT will accelerate as more intelligence is pushed to the edge, especially in the form of new AI inference chips and more decentralized networks,” continues Davies. “This will result in more-complex entities outside of the organization that are able to ‘reason,’ as well as greater chatter among things.”

However, due to the immaturity of thinking on the IoT, early adopters will have limited evidence on which to base their own best practices. Another potential stumbling block is that the anthropomorphization of things will likely span multiple departments including CRM, digital workplace, innovation, IT, marketing and multiple other business units. The ensuing cultural, political and technical hurdles could all complicate progress.

As things become more autonomous — and are better able to take actions independent of humans — the ability for things to provide feedback to other things will help accelerate their learning and subsequent performance.

Source: Smarter with Gartner